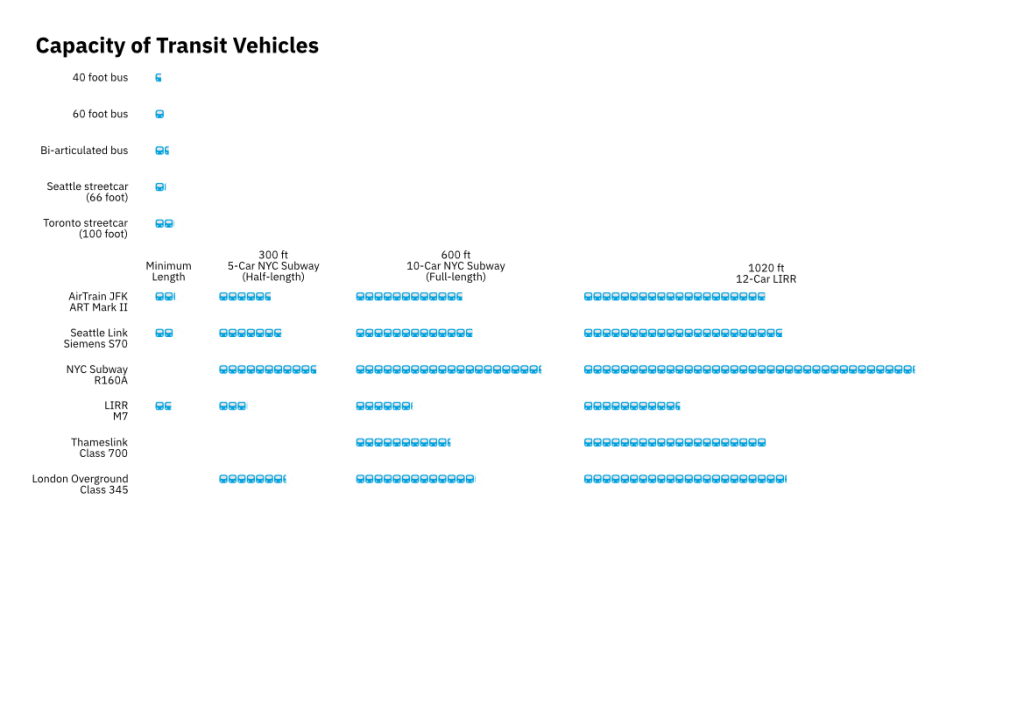

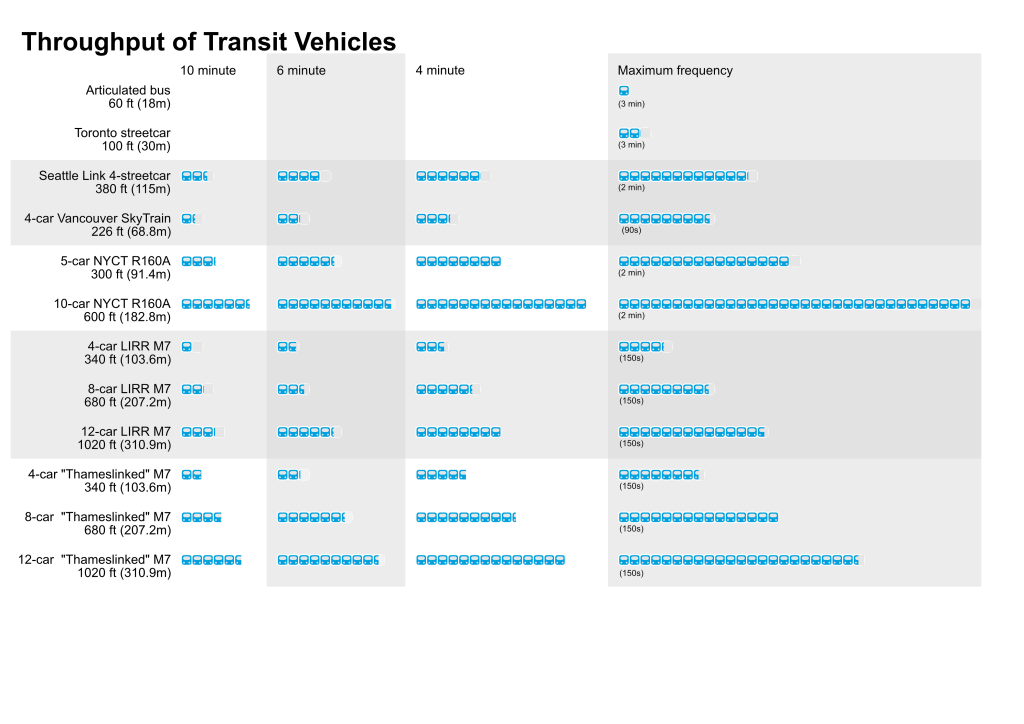

This post follows my post on the capacity of individual vehicles. To keep this post at a reasonable length, this post discusses only certain combinations of frequency and vehicles, and will be limited to combinations that would reasonably deployed in New York City.

Street running lines

This category of vehicle is defined as any line, rail or bus, that features regular intersections with traffic regulated by traffic lights. Generally speaking, the upper limit here is a vehicle every 3-4 minutes; any more frequent and you will either suffer excessive bunching as vehicles continually catch up and leapfrog each other, or require crossing gates that would be down for an unacceptable amount of time.

A 60 ft (18m) articulated bus running every 3 minutes (20 vehicles an hour) would carry 2400 people per hour per direction (pphd).

A 100 ft (30m) Toronto streetcar running every 3 minutes would carry 5020 pphd.

Grade separated lines

Grade separated lines are those that are completely separated from crossing traffic. This enables higher frequencies without having to worry about getting in the way of crossing traffic, or vice versa.

Seattle Link Light Rail, in its central sections, is basically a subway that happens to use coupled tram vehicles. The plan is to run, on the central segment, 4 trams coupled together measuring a total 380 ft (115m). At the planned 4 minute headway, this will be 14,580 pphd; it is possible to double this frequency for a total of 29,160 pphd.

The Vancouver SkyTrain uses 113ft (34.4m) Mark II ART vehicles like those found on the AirTrain JFK. As an automated system, it has a signalling system that can handle 90s headway. At the 4-car configuration this would be 20,480 pphd.

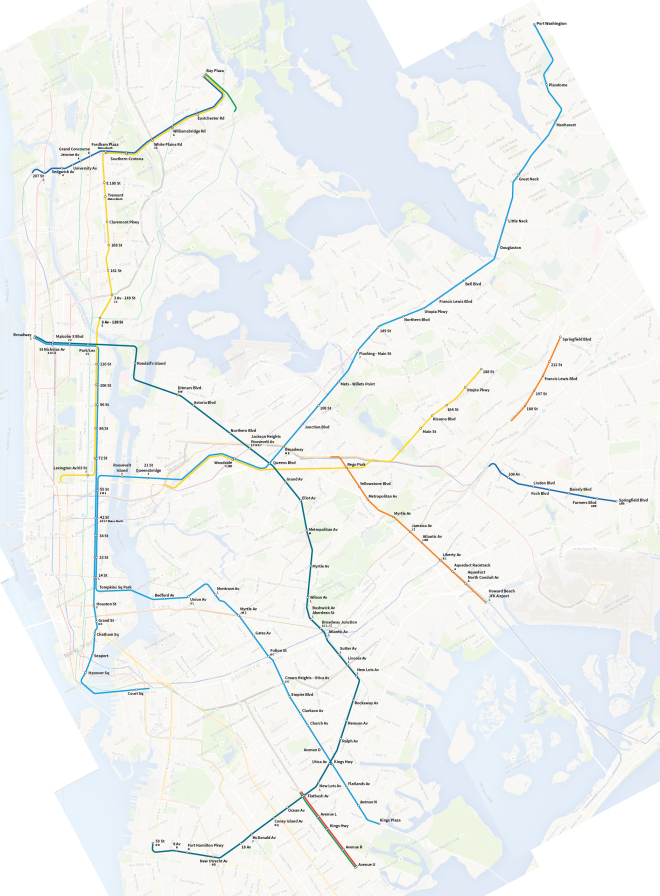

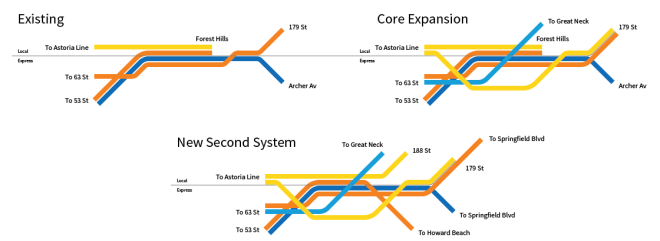

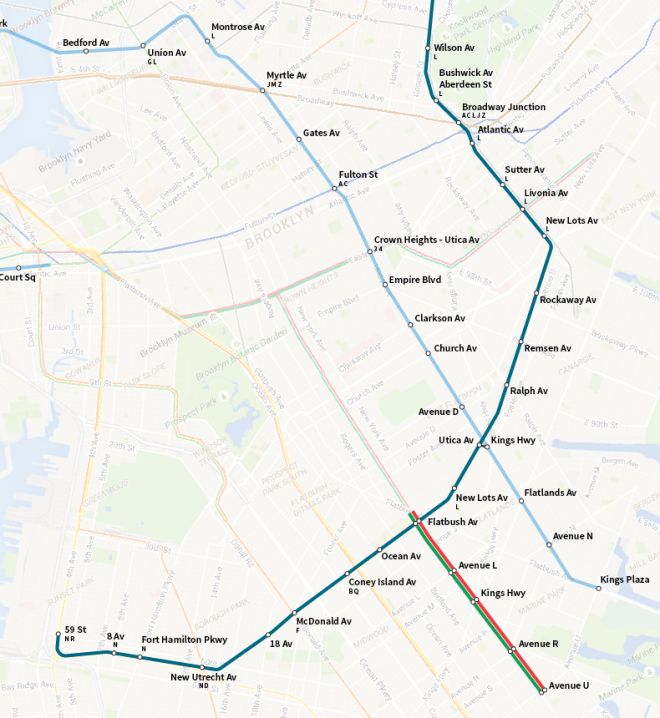

The NYC Subway runs trains consisting of two 5-car R160A sets, each 300 ft (91.4m). A 5-car set every 10, 6, 4 and 2 minutes, this would represent 7686, 12,810, 19,215, and 38,430 pphd; and the 10-car configuration would double all these numbers.

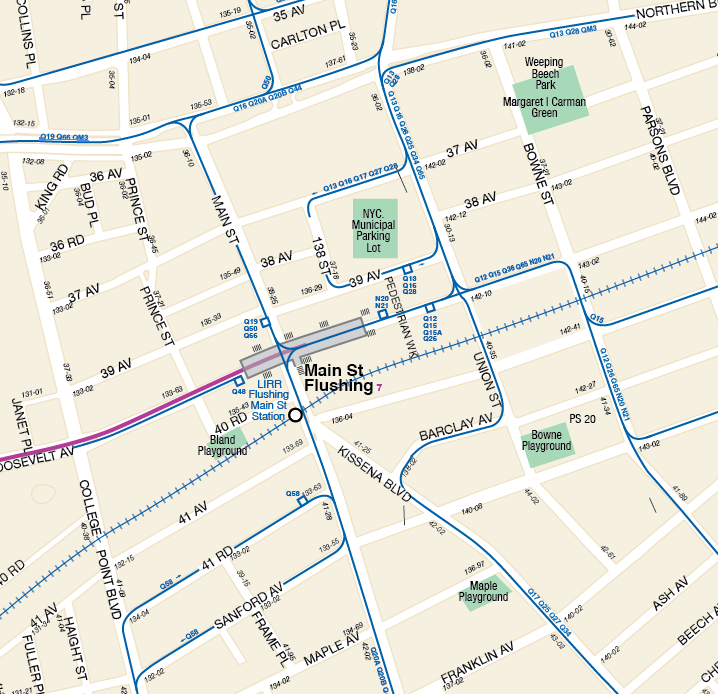

The LIRR runs 2-car “married pair” sets 170 ft (51.8m) long characterized by generous seating and little standing room. A 4-car set running every 10, 6, 4, and at a railroad’s maximum frequency of 24 trains per hour has a capacity of 2,532, 4,220, 6,330, and 10,128 pphd. The LIRR runs these trains in up to a 12-car configuration, so these numbers would be tripled.

Thameslink is a regional rail service in London that runs fairly long train routes. It has slightly less generous seating than LIRR in a 2×2 configuration in its standard class, but has ample standing room by doors and in the aisles. Extrapolating its capacity to the LIRR’s 4-car trainset size, that would be 4495, 7591, 11237, and 17980 pphd respectively.

Notable omissions

Buses in other parts of the world, most notably South America, can run at high enough frequencies to have capacity rivalling those of high-capacity subways. However, this requires passing lanes for buses to be able to pass each other and full separation from traffic; at that point, the “bus lane” resembles a mini-highway, and the odds of blasting new highway-like roads through NYC is basically zero.

I’ve listed the maximum frequency of the subway as every 2 minutes. This is the currently scheduled maximum trains on a pair of tracks anywhere in the NYC subway; however, there are projects in the works to upgrade various lines to the same type of signalling used on the Vancouver SkyTrain. As of this writing, I am not aware of what the final capacity of the new CBTC project is, but I would imagine it’s lower than a train every 90s given the subway’s more complex service patterns and the requirement for some trains to switch from CBTC to traditional signalling and vice versa.

In the capacity post I listed bi-articulated buses and London Overground rail trains as examples of high-capacity vehicles, but throughput for these vehicles is not listed in this post. For the former, there is currently no low-floor bi-articulated bus operated in North America, and the small size of the American transit market and the vehicle’s already small niche make it unlikely to be widely used. For the latter, converting LIRR trains from abundant 3×2 seating to subway-style bench seating would be politically poisonous.

Below is an image to illustrate the relative differences in capacity.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/gta/2015/10/28/ttc-will-sue-bombardier-over-late-streetcars/ttcnewstreetcar-creditttcjpg.jpg)